Five months into my eight-month solitary confinement and right before the Persian New Year, Nowruz, the guards put me in a new cell at the other end of the Evin prison high-security facility in Tehran. Measuring 3 by 3 meters, it was much larger than my old cell, which meant I could walk in a figure eight across the corners. In the absence of anything else to do, continuous walks were my sole routine, and they quickly became an addiction.

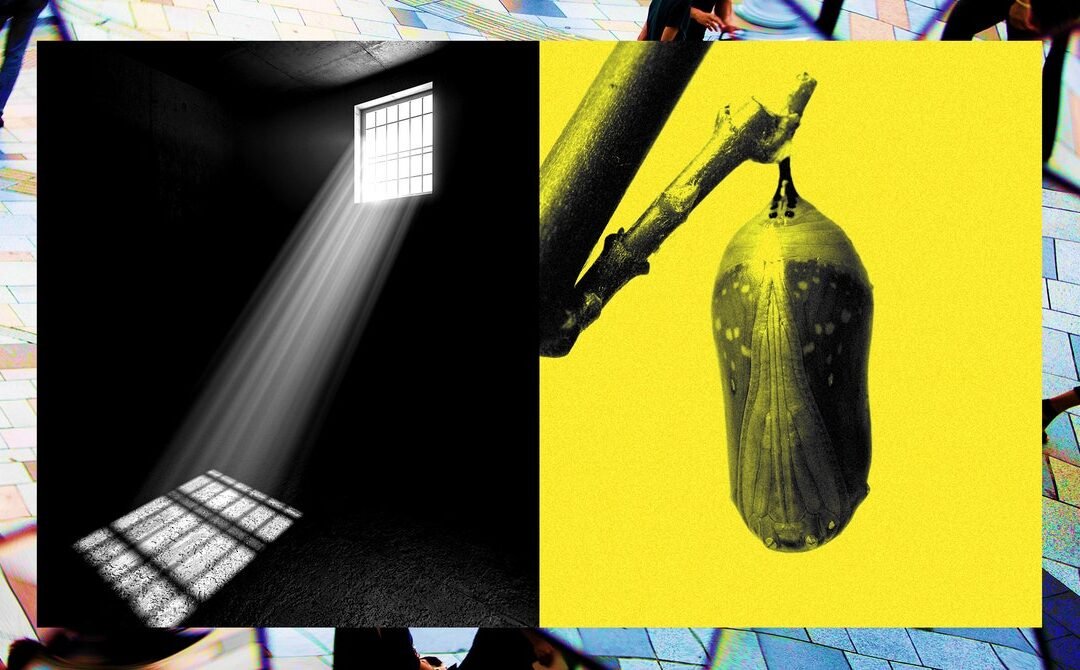

I walked and walked. Remembered and imagined, anticipated and planned for all possible scenarios, and often conversed with myself out loud, in any languages I had any knowledge of. During these figure-eight walks, I faced the windows or the half-marble-covered walls. Sunlight seeped into the room, tracing paths of gold over the floor, then scaling the walls. It danced, warmed, then vanished, promising to return tomorrow. The marble canvas revealed images: the curved, nude back of a seated woman, surrounded by profiles of faces and clouds.

Deprived of sights, I sought refuge in sounds. The new cell received less light due to the tall, gorgeous plane and mulberry trees right outside. but it was right next to the main entrance and thus, within Evin standards, more eventful and entertaining—even if only through hearing. I could hear when the bored guards gossiped about their shift supervisors at the end of the hall, or when they responded to other inmates’ requests, or when they watched football or drama on state television. (I never heard any news, since they were strictly advised not to watch the news.) Once, a few seconds of an instrumental version of Radiohead’s “A Punch Up at a Wedding” on a stupid TV commercial made me cry my heart out. I wasn’t sure which I craved more: hugs or books. I suspect it is very rare to be deprived of both at the same time.

My only comfort came from our equality in this misery, or at least the perception of it. The guards and interrogators had always said no one was given books or newspapers in our ward. I had believed them, because I had seen no sight (nor heard any sound) of them.

One afternoon, though, I heard something that shattered this tiny comfort. Four pairs of slippers had appeared outside a cell two down from me, hinting at four inmates who most likely had just come out of solitary to be kept in a large cell together. A few hours later, through the ventilation shafts that connected the cells, I heard newspaper rustling. It broke my heart, truly. That common shaft and what I could hear through it deeply unsettled me for the next three months. Of all the injustices of a high-security prison ward, from the blindfolded walking breaks in the yard to the awful gray polyester uniform and the cheap blue nylon underwear, this one felt the harshest.

But what if there were no shared ventilation shafts between cells via which I heard the other cell? What if the ward were so vast that we never felt the presence of others? What if they could make us deaf as they made us blind? What if they could enclose our senses as they trapped our bodies? Broader questions emerge: If we know nothing about our colleagues’ salaries or where and with which standards they live, can we even know if we are treated fairly? Can injustice be felt if there is not a shared space where we can see and learn about others’ lives?